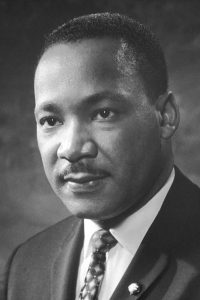

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Table Of Contents

In the world of civil rights in The United States of America, there is only one name that stands out above all others: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. His determination was unparalleled and his bravery unmatched, which is why he’s become an iconic figure in United States history. He spent his life fighting for equality between races, a goal that we are still working towards to this day.

Martin Luther King Jr. was an African American Baptist minister and activist who became the most visible spokesperson and leader in the American civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968. He did this by using nonviolent resistance and activism, inspired by his Christian beliefs and Mahatma Gandhi. Martin Luther King Jr., also known as Dr. King, led marches for blacks’ right to vote, desegregation, labor rights.

He has been called one of America’s greatest orators, and his speeches are still being studied today. His 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech is one of the most famous pieces of public speaking in history, and it helped lead to the passage of The Voting Rights Act that same year.

What Did Martin Luther King Jr. Do?

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is a hero who has done many great things in American History. Some examples would be;

He helped to found the Montgomery Improvement Association, which led boycotts against segregated public transportation. He also was a leader of the Civil Rights Movement and helped lead many marches for equality in America.

He founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

He won the Nobel Peace Prize

Established The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

Organized Mississippi Freedom Summer Project with James Bevel and John Lewis

When was Martin Luther King Jr. Born?

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was born January 15th, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, to Reverend Martin Luthar King Sr., and Alberta Williams King.

What is Martin Luther King, Jr., known for?

Dr. King’s legacy includes The Civil Rights Act of 1964 (the most sweeping civil rights legislation since Reconstruction) the Voting Rights Act 1965; he also helped launch a movement, which changed America by bringing an end to discrimination against African Americans in public places such as restaurants and hotels.

What Did Dr. Martin Luther King Jr accomplish?

Martin Luther King, Jr. had many accomplishments and was very active his entire life fighting for black people’s rights. He fought to get the Montgomery Bus Boycott started which made it illegal to segregate on buses in Alabama. The boycott ended after 38 months because of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s leadership skills and how he ran meetings where protesters would be educated about their role as citizens during that time period and what they could do to help change things such as boycott companies who supported segregation or sign petitions against unfair laws like the Jim Crow Laws which were discriminatory towards blacks living in southern states such as Texas, Arkansas, Mississippi or Louisiana at that time.

Who did Martin Luther King, Jr., influence, and in what ways?

Martin Luther King, Jr., has influenced people from all around the world. He advocated for peaceful approaches to some of society’s biggest problems. He organized a number of marches and protests against racism, injustice, segregation, and played a pivotal role in the American civil rights movement. His legacy is so important to American history that there is a holiday honoring Dr. King Jr. yearly in January. He was also posthumously awarded the Nobel Peace Prize on December 11th of 1967.

What was Martin Luther King’s family life like?

Martin Luther King Jr’s family life was filled with love and care.

He was the youngest of four children born to Alberta Williams King and Reverend Martin Luther King Sr. His parents encouraged him to gain an education, despite their financial difficulties at times. The family valued hard work, humility, faithfulness in marriage, academic prowess, and many other key moral values that they taught young Martin through example.

How did Martin Luther King, Jr., die?

Martin Luther King Jr . was assassinated on April 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee. He had gone to Memphis to lead a protest march of sanitation workers who were mostly African-American and did not have sufficient pay or safety equipment.

It is believed that these public protests against racial discrimination were one reason why Dr. Martin Luther King Jr met with an unfortunate end. He led marches all over America, such as in Birmingham, Alabama, where he participated in peaceful demonstrations only to be confronted violently by policemen using dogs and water cannons.

On the evening before his death, he gave a sermon at Mason Temple. A few hours later, he stepped out on the balcony outside Room 306 of the Lorraine Motel when shots rang out from nearby bushes below by James Earl Ray who was responsible for the mlk assassination.

King was taken to the hospital and died there at age 39.

King died at St. Joseph’s hospital an hour later. King is remembered not only with memorials but also with over 800 streets across the country named after him.

James Earl Ray had escaped from prison in 1967 but never revealed whether he assassinated Martin Luther King Jr., or if somebody else did it on his orders.

1964 Civil Rights Act

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a landmark law in the history of civil rights legislation in this country and was signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson. This piece of legislation passed by U.S. Congress outlawed racial discrimination in employment, public accommodations, and other aspects of American society. It is often seen as the most important law since Reconstruction due to its profound impact on African-Americans’ lives. The bill finally made it illegal for employers and business owners to discriminate against someone based on their race or skin color; public facilities such as hotels, restaurants, theaters were forced to desegregate with “all deliberate speed” (meaning they need not be completely integrated at once); all citizens would have equal access to voting polls without regard to race; schools could no longer segregate students by creating separate classrooms or playgrounds for black children only.

The Montgomery bus boycott

The Montgomery bus boycott is arguably the single most important event in American history in terms of civil rights. The boycott was planned by a group of African Americans led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The boycott started on December 1955 and lasted 38 months until it ended with an agreement that is known as “The Modification Agreement”.

The Modification Agreement required Montgomery to desegregate city buses, provide equal and uniform service for all passengers; replace drivers with courteous operators who a committee of African Americans screened.

During the boycott, Dr. King’s wife Coretta Scott King, was the only woman among those arrested on January 18th, 1956, when she refused to obey an officer’s request that she give up her seat in defiance of segregation laws that mandated whites-only seating areas. This boycott is also seen as one of the first successful large-scale boycotts anywhere in modern history. It became a model for many other organizing efforts around the world, such as India’s independence movement under Mohandas.

Personal Life

In June 1953 King married Coretta Scott. They had four children, Yolanda Denise King (b. 1957), Martin Luther III (b. 1961), Dexter Scott King (b. 1963) and Bernice Albertine King (died in infancy). In 1955 the Kings bought their first house in Atlanta’s Vine City neighborhood.

The Kings were part of a significant social circle that included both whites and blacks, including Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, Quincy Jones, Lena Horne and the comedian Dick Gregory. King was also friends with Billy Graham’s son Franklin. Graham named King “the single most powerful force for Negro equality in America in his memoirs.”

In 1957 King became pastor of Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church while still holding down an academic job teaching religion at nearby Morehouse College. He would eventually become president of the church but kept on as professor until 1960 when he resigned from Morehouse to devote himself full-time to his ministerial duties.

Education

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s education is a large part of who he was as an individual. Martin Luther King Jr’s education began at age six when his family moved to Atlanta, Georgia in 1918, and attended segregated schools as a top student. He attended Booker T Washington High School from 1928-1935 where he participated in many extracurricular activities such as debate club, football team, and school newspaper “The Pride”.

Martin Luther King Jr’s first degree came from Morehouse College, which is also located in Atlanta (graduated with Bachelor of Arts). Afterward, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr studied philosophy up north at Crozer Theological Seminary outside Philadelphia, Pennsylvania graduating with another bachelor’s degree, this time in theology.

I Have A Dream Speech

– Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., delivered his famous “I Have A Dream Speech” on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. After he was finished, over 250,000 people stood up to applaud him for over 12 minutes. This speech has become one of the best-known speeches in history because it symbolizes unity, equality, progressive values

– This speech had a profound effect on America and has been called one of the most important speeches ever made in American history because it is an excellent example of nonviolent civil disobedience that led to change, which would not have happened otherwise.

You can read or watch the entire “I Have A Dream” Speech here

The Three Dimensions Of A Complete Life Speech

– This speech was delivered on April 9th, 1967 at the New Covenant Baptist Church in Chicago, IL.

Dr. King Jr.’s legacy is one that will not be forgotten anytime soon because of his determination and selflessness, which made him a hero for everyone who loves freedom as much as he did.

We’ll never forget the contributions that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. made to us all and the world in general, which is why he will always be remembered as a hero for civil rights movements everywhere.

We would not have had such an impactful change without someone who cared as much as Dr. King did, which is why he will always be remembered as our hero, long after all other men are forgotten- thanks to his determination and selflessness, which helped make us free.